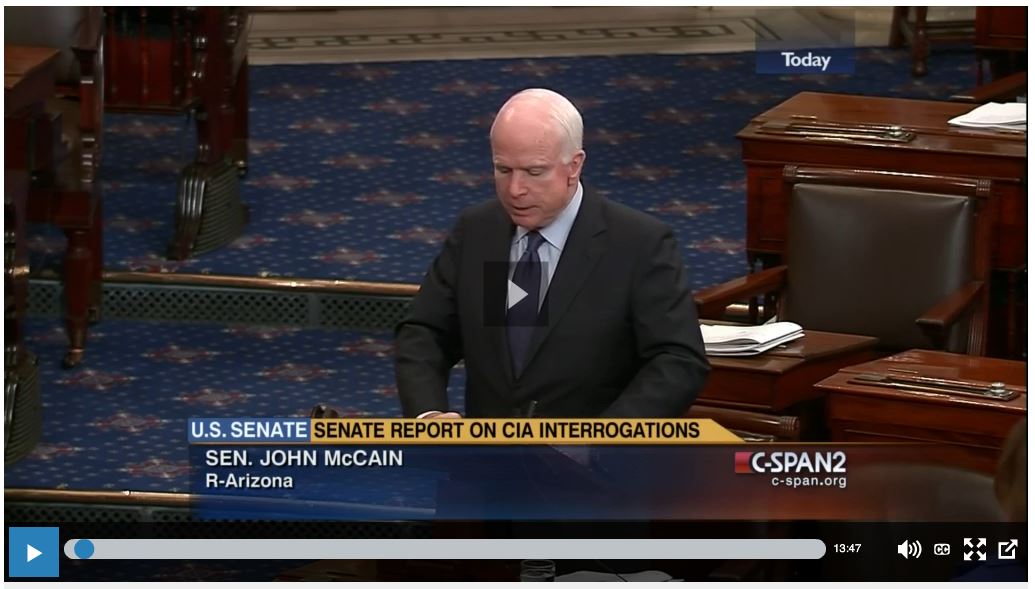

There was considerable misinformation disseminated then about what was and wasn’t achieved using these methods in an effort to discourage support for the legislation. There was a good amount of misinformation used in 2011 to credit the use of methods with the death of Osama Bin Laden, and there is, I fear, misinformation being used today to prevent the release of this report, disputing its findings and warning about the security consequences of their public disclosure.

With the report’s release, will the report’s release cause outrage that leads to violence in some parts of the Muslim world? Yes, I suppose that’s possible, perhaps likely. Sadly, violence needs little incentive in some quarters of the world today. But that doesn’t mean we will be telling the world something it will be shocked to learn. The entire world already knows that we waterboarded prisoners. It knows we subjected prisoners to various other types of degrading treatment. It knows we used black sites, secret prisons. Those practices haven’t been a secret for a decade. Terrorists might use the report’s reidentification of the practices as an excuse to attack Americans, but they hardly need an excuse for that. That has been their life’s calling for a while now.

What might cause a surprise not just to our enemies, but to many Americans is how little these practices did to aid our efforts to bring 9/11 culprits to justice and to find and prevent terrorist attacks today and tomorrow. That could be a real surprise since it contradicts the many assurances provided by intelligence officials on the record and in private that enhanced interrogation techniques were indispensable in the war against terrorism.

And I suspect the objection of those same officials to the release of this report is really focused on that disclosure; torture’s ineffectiveness. Because we gave up much in the expectation that torture would make us safer. Too much. Obviously, we need intelligence to defeat our enemies, but we need reliable intelligence. Torture produces more misleading information than actionable intelligence. And what the advocates of harsh and cruel interrogation methods have never established is that we couldn’t have gathered as good or more reliable intelligence from using humane methods. The most important lead we got in the search for Osama Bin Laden came from conventional interrogation methods. I think it’s an insult to the many intelligence officers who have acquired good intelligence without hurting or degrading suspects. Yes, we can and we will.

But in the end, torture’s failure to serve its intended purpose isn’t the main reason to oppose its use. I have often said and will always maintain that this question isn’t about our enemies, it’s about us. It’s about who we were, who we are and who we aspire to be.