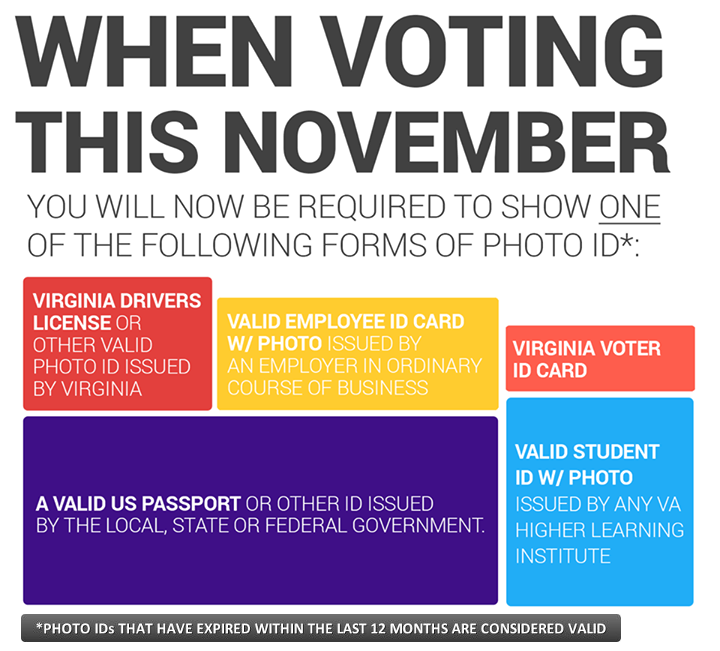

About 300,000 Virginia voters lack an ID issued by the state Department of Motor Vehicles. Voters can obtain a free photo ID from any local registrar’s office. More information can be obtained by visiting www.GotIDVirginia.org or by calling the election protection hotline at 1-866-687-8683 (OUR-VOTE).

Virginia is in week seven of its new voter photo ID law, and just last week state election officials narrowed the rule for what will count at the polls as valid ID. Voters may well be unsure if they have what they’ll need to cast a ballot.

We hope any confusion can be dispelled in time for this November’s general election. It is an important one that will decide who will represent Virginians in Congress.

What a bitter irony it would be if difficulty in meeting the new requirement, or just uncertainty about the new law, kept a significant number of voters away from the polls.

Both the new voter photo ID law and the newly restrictive rule for implementing it are children of a theory: That people can easily claim to be someone they are not and vote in their stead, and do so.

Not every theory is necessarily valid.

State lawmakers succeeded this year in passing a photo ID law to ensure fair elections — and a nobler purpose could hardly be put forward in a representative democracy. Free and fair elections give elected government its legitimacy.

And yet, there has been no evidence that voting fraud of any kind has influenced the outcome of a Virginia election, much less in-person voter fraud by someone claiming to be who he (or she) is not.

The new law does not solve an identified problem — but it can create one, especially for frail elderly or disabled people who have difficulty getting out and about.

If state lawmakers want to assure the integrity of the ballot box, they would do better to look elsewhere for fraud, because studies have shown that attempts at voter impersonation at the polls hardly ever happen. The likelihood of voter fraud is far higher with absentee ballots, which can gather in many more votes with far less trouble.

So says a Loyola University Law School professor whose recent guest contribution on The Washington Post’s Wonkblog is entitled: “A comprehensive investigation of voter impersonation finds 31 credible incidents out of one billion ballots cast.”

For years, Justin Levitt has been looking into “any specific, credible allegation that someone may have pretended to be someone else at the polls, in any way that an ID law could fix.”

Such laws, he points out, “aren’t designed to stop fraud with absentee ballots (indeed, laws requiring ID at the polls push more people into the absentee system, where there are plenty of real dangers).”

Yet that is precisely the fix that the sponsor of Virginia’s voter ID law, Sen. Mark Obenshain, suggested to Roanoke Times columnist Dan Casey when he spoke last month to Obenshain about the hassles the law creates for older voters who are not so mobile anymore.

Elections are, indeed, sacrosanct — or should be. Fraud should never be tolerated.

What purpose truly was served last week, though, when state election officials, at Obenshain’s behest, reversed a sensible accommodation to allow expired driver’s licenses and passports to serve as photo IDs? People’s driving privileges can expire, their ability to travel may become limited, but their identities do not change.

The board set an arbitrary limit on the credentials: If they expired more than 12 months before Election Day, they won’t get a registered voter into the voting booth.

Virginians eligible to vote should not be daunted by the hurdles. People can learn what other forms of photo ID are acceptable on the state elections board website or by calling their local registrar’s office. Mobile outreach also is scheduled in some localities over the next 60 days for people lacking any acceptable ID.

And like the man says, there’s always absentee voting by mail.

via the Roanoke Times